< <

<

All

>

> >

Analyzing the 2020 Election

The big question is - did the election of 2020 exhibit any unusual patterns of votes?

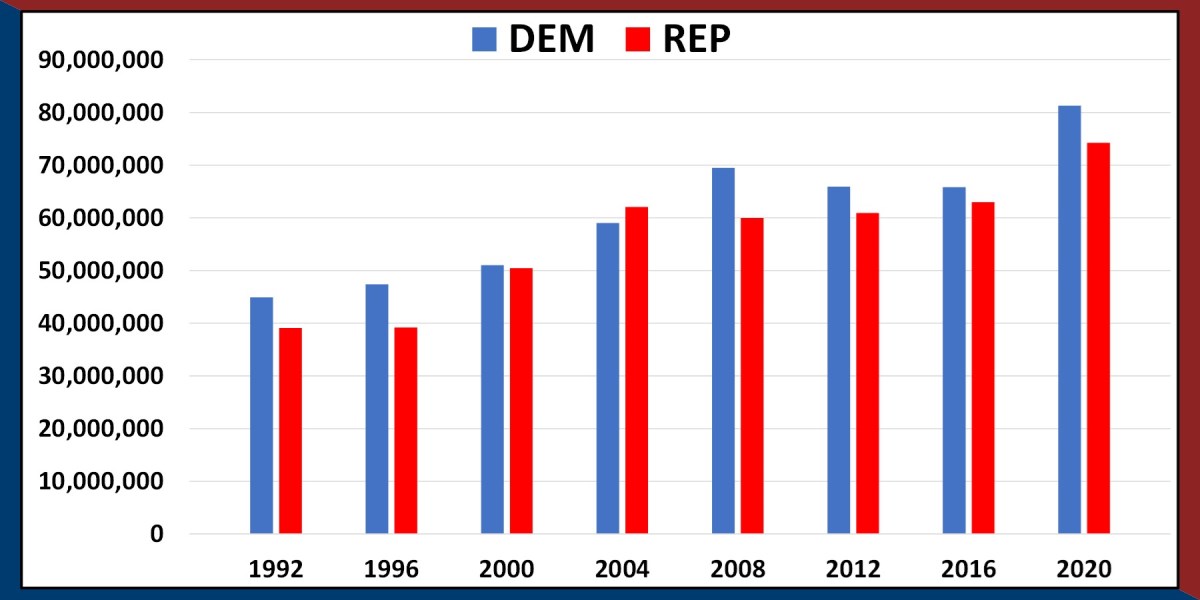

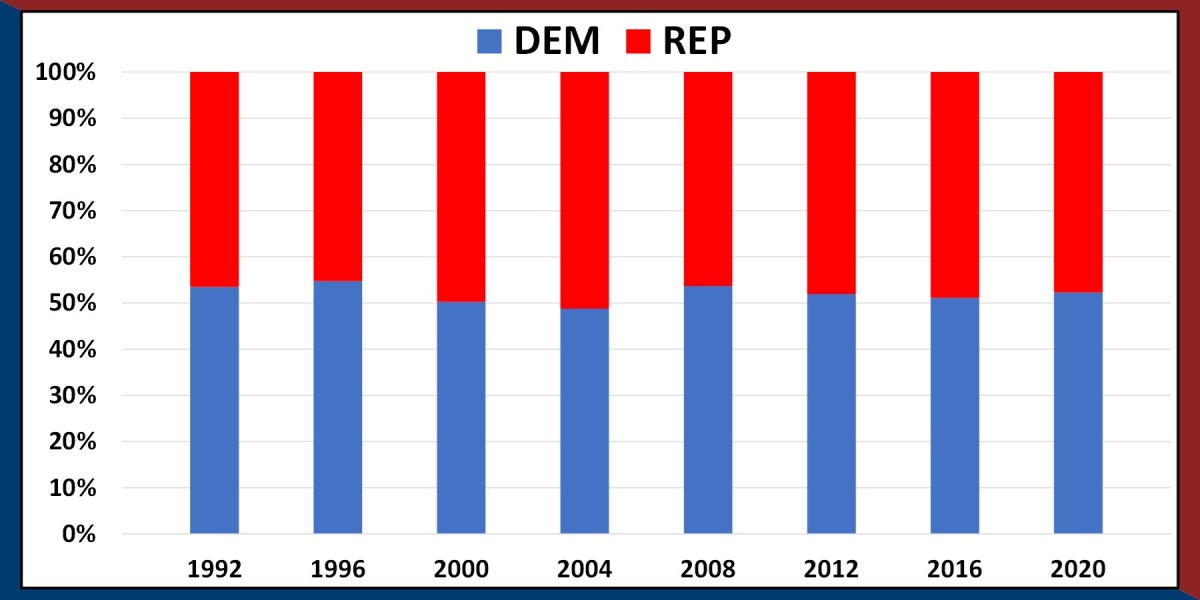

First, when we look at the popular vote, how did the numbers for Biden and Trump look? In general, the overall number of votes increases because the population of the nation increases. We can see that the overall turnout in 2020 was much higher than the previous two elections which is likely driven by the combination of the extremely contentious election and the fact that the covid-19 pandemic caused many states to expand their mail-in and early voting procedures. Even so, it's pretty much what we would expect if the trend line from 1996-2008 had continued. The margin of victory for Biden seems like an average of Obama's two elections and on par with Clinton's victories in the 1990s - it seems pretty typical for the margin when a Democrat wins.

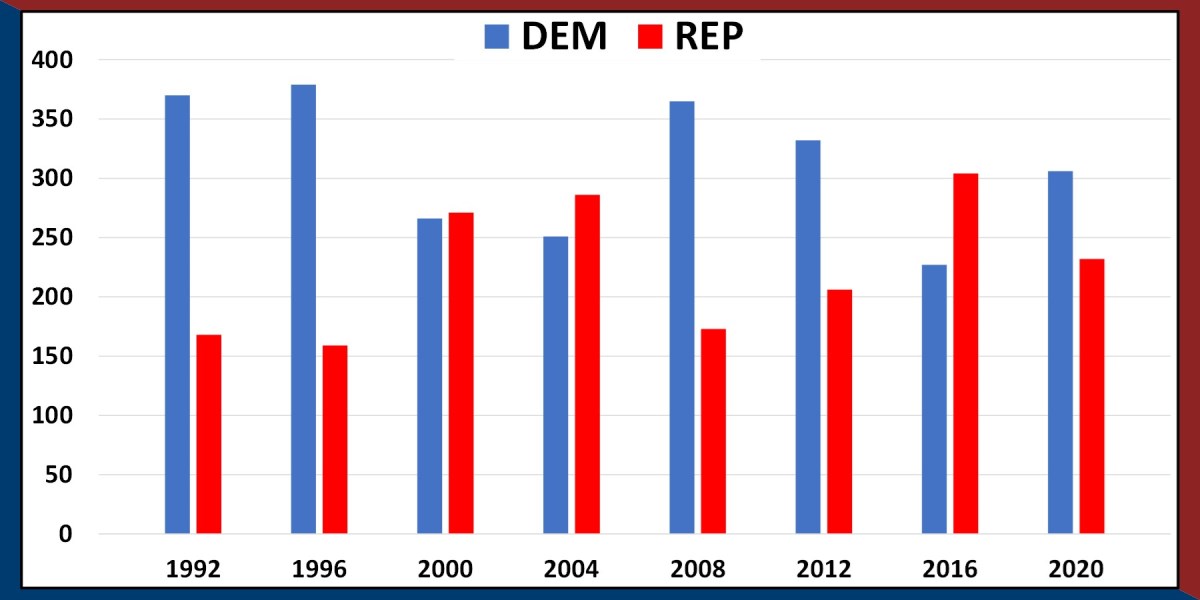

From looking at the popular vote totals there is no evidence of voter fraud or unusual vote numbers. Also, the Electoral College vote totals are in line with exactly what we expect based on the voting observed.

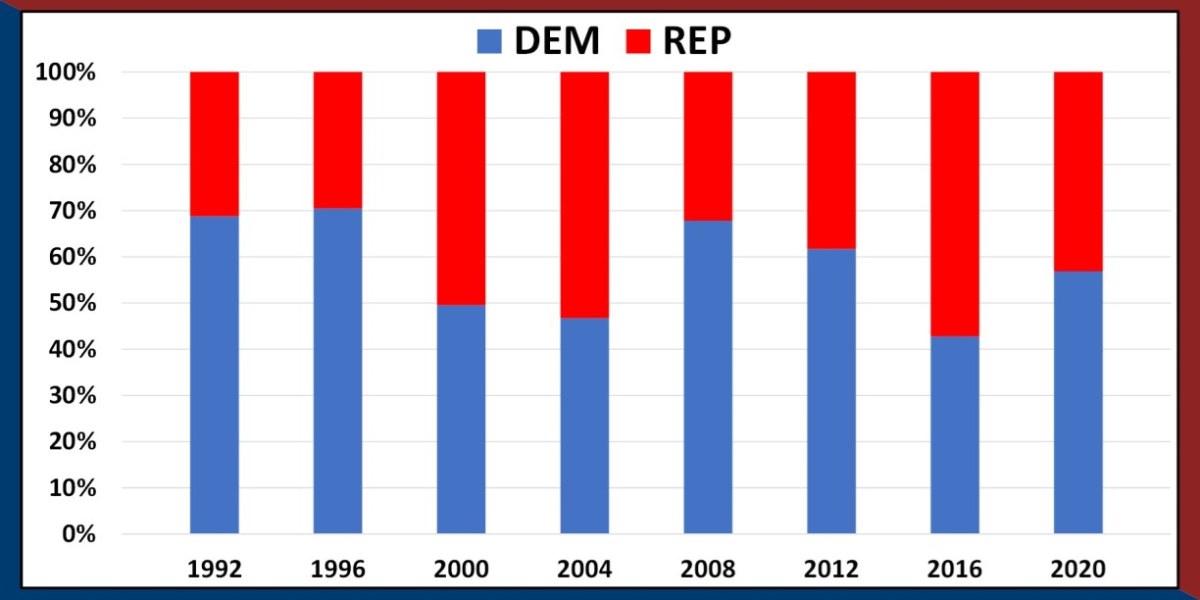

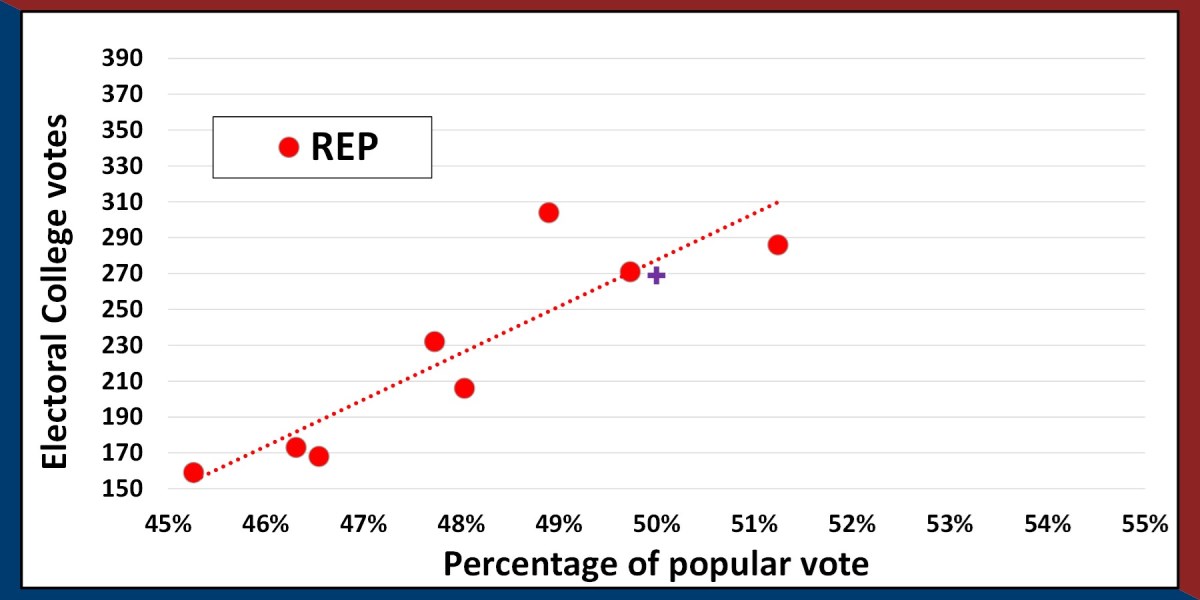

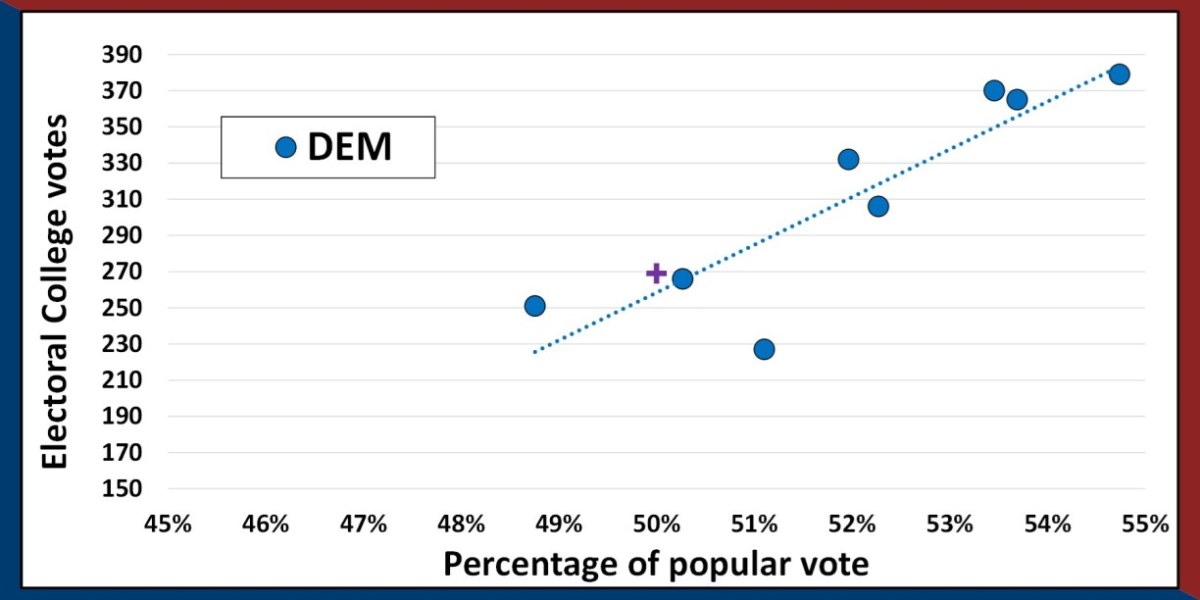

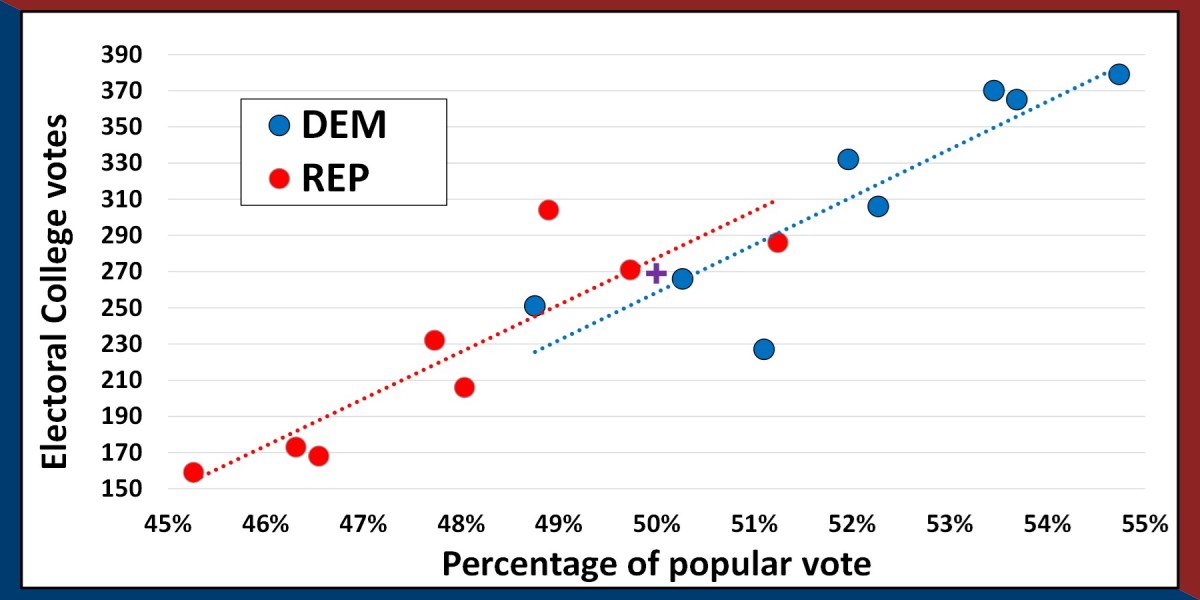

This occasional mismatch between the popular vote and Electoral College vote is interesting. The Electoral College was designed to be a mechanism with the primary purpose of representing the popular vote when communication technology was primitive (there are some details about preserving slavery and representing rural citizens that we won't go into). How well does the electoral college vote represent the popular vote? We can look at this in the two figures below where the percentage of the popular vote in plotted on the X-axis and the percentage of the Electoral College vote is plotted on the Y-axis. If the representation conferred by the Electoral College is perfectly accurate then the data points for each election would lie directly on the best-fit line which would go through the origin and the point (50%, 269 Electoral College votes). In the plots below we can see that there is considerable noise. Neither Republican nor Democratic votes are being consistently represented by the Electoral College. There are some elections where the number of electoral college votes each party gets are more or less than expected based on the overall relationship between the popular vote and Electoral College vote. On neither plot does the relationship go through the point (50, 269) which is marked with the purple "+" symbol.

This bias, plus the added randomness from the Electoral College explains how the Republicans have only won the popular vote once in the last 8 elections, but won the presidency 3 times.

< <

<

All

>

> >

Connect with StatsExamples here

This information is intended for the greater good; please use statistics responsibly.